How Characters Come Alive

Interview with Chris Avellone: Part I

Chris Avellone thinks in character. Almost everything he writes is rooted in this thinking of how characters come to inhabit people’s minds. There are many great RPG writers, but few writers have embodied this character-driven ethos in their game design as much as Avellone did since his first 1990s credits as a designer and writer at Black Isle Studios. He was also a founding figure at Obsidian Entertainment, who shaped their game design philosophy as a creation process for unique characters and a willingness to take risks with those characters.

The past few years have been a whirlwind, but this interview is about the here and now of an industry beset with uncertainties and crises. As the world scrambles to adjust to a new technology and a new artificial reality, there is a core factor of game design that remains profoundly human. It is a factor that cannot be easily simulated or automated by the possibilities of training data models. That is the irreplaceable role of character.

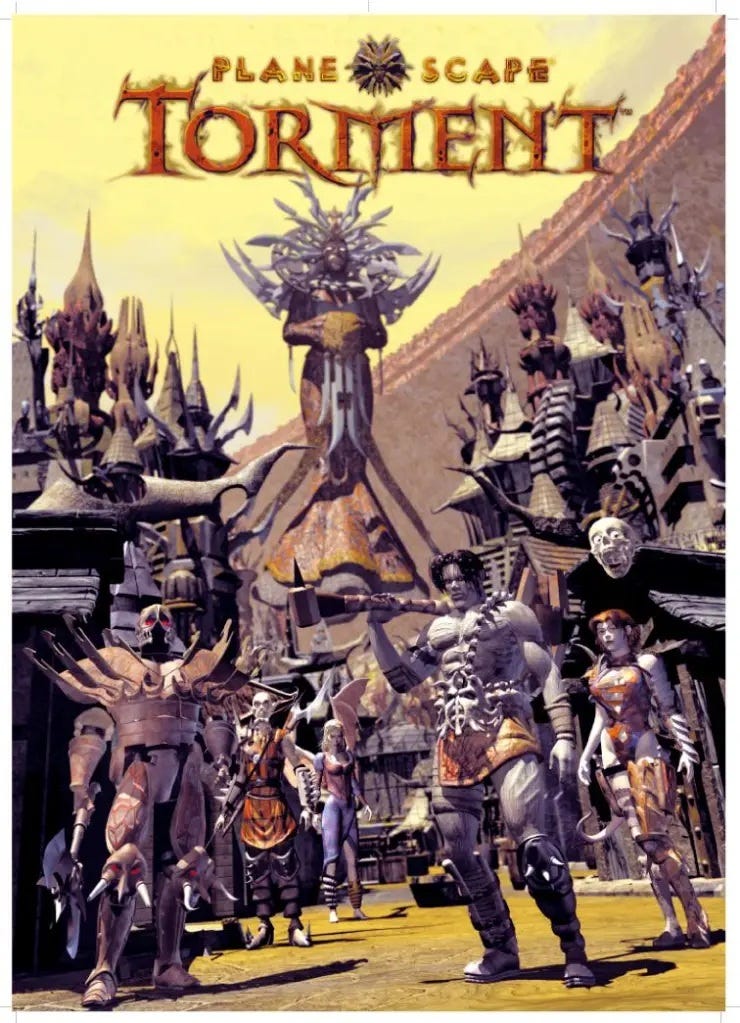

This interview will be published in two parts, and this first part will be grounded in one character in particular: Annah-of-the Shadows, a tiefling thief in Planescape: Torment. Any reader unfamiliar with the world of Planescape in the overarching mythology of Dungeons & Dragons might feel lost, but even writers and players who spent years thinking about these worlds don’t understand them entirely.

The Setup

Avellone was kind enough to write a few thousand words in response to my questions, and I include the responses with some personal commentary to add my own perspective as a player and aficionado of character development. I began the interview with the story of a friend in Edmonton, Max Dickeson, who was born without sight. His perspective on Annah was one of the starting points for this interview.

Max is a highly competent DM running 5E campaigns in his own homebrew universe. A few years ago, when we first started hanging out, he asked about my top RPGs, and I mentioned Planescape: Torment first. He’d never played it, but he’d read a document online with all of Annah-of-the-Shadows’ lines and content. Max studied this closely because he’d heard she was one of the most memorable characters in RPG history.

My first question to Avellone was: “What makes Annah endure?” She appeared long before explicit discourse on representation or strong female characters in games. Yet she’s always felt psychologically real, emotionally alive: abrasive, vulnerable, human. How did he begin to build that complexity? What guided her voice, her bond with the Nameless One, her place in that world? Was there a conscious push against tropes, or did her depth emerge organically?

How Annah Came Alive

Avellone tells the story of Annah’s creation as a multifaceted and complex process, less motivated by one single approach or factor. There is no shortcut to character complexity, and engaging with that complexity from many angles and perspectives was a necessary step in creating a character like Annah.

Her creation came both organically and from pushing against tropes, but it also included embracing some tropes. Also, I had help from Annah herself.

To explain, one thing that happens as a writer is once you establish what you believe to be the foundation for a character, that character starts writing their own story based on that foundation… and often, the character can get away from you. Ravel, also from Torment, definitely did and became far more important to the plot over time.

Annah was no exception – once you know someone’s background and their personality traits, skills, and so on, they’ll start making story decisions for themselves.

Method actors have a similar process that allows the emergence of the characters on their own terms, rather than the actor’s terms. Writing is different from acting in many ways, but there is an overlap in how actors enact their characters and how writers develop theirs. The feeling for what would be out of character becomes intuitive, not something that can fit into a simple scheme or algorithm.

Rogue’s Gallery

Annah is one of the several companions that The Nameless One, the player character, can recruit and interact with as they progress through the game. Companions are never isolated in a room with the player; they exist in relationships with other companions as much as with the player character. The companions for Planescape: Torment remain one of the blueprints for companion design in Western RPGs.

Now another thing that builds upon a companion character’s own “voice” and autonomy is if there’s also other similarly-detailed characters in the party, say in even an atypical D&D party like Torment, the other companions will act as sounding boards for each other… and then their reactions to each other can also start making story decisions. So over time, even through companion exchanges, Annah developed more and more detail, just like the other characters.

In terms of how Annah came to “be,” I’ll start with a pragmatic answer. Usually the example I’ve used for this breakdown in the past has been Morte in Torment (and the answer was, “hey we needed a mimir [a Planescape encyclopedia shaped like a skull, it’s part of the franchise] to explain everything, but we wanted it to have a personality, and someone you could relate to if you were a stranger to the universe, oh, and since you get him early on, having him be able to tank and soak up damage is good,” and so on), but the same step-follows-step process was true for Annah as well.

The relationships between the characters are not accidental or superfluous; they are essential for each character to develop and serve their purpose in the story. Morte’s role as a mimir is not only an exposition device but also an engine for character development. Morte and Annah have a particularly prickly relationship that drives the story to something more lifelike, bickering as true friends do.

System Flock

Planescape: Torment was based on the Advanced Dungeons & Dragons 2nd Edition ruleset, which differs radically from subsequent editions, featuring the now-obsolete THAC0 system. The narrative focus of Torment also entailed tweaks, such as highlighting exotic races and simplifying class progression, but retained core mechanics like THAC0, proficiencies, and saving throws. Avellone confirms how some system constraints contributed to character development:

We started with some system constraints:

- In general, you want companions that represent a range of personalities, races, representatives of castes/factions important to the game, and so on. As such, we knew we had “human,” githzerai, “mimir,” tanar’ri, etc. so whoever we made needed to complement the existing structure and give everyone a chance to shine.

- We wanted a tiefling in the party because tieflings are a big part of Planescape.

- We wanted a thief to represent the skills of that class.

- In addition, the very nature of designing a “companion” come with a list of traits to be considered (which I’ll elaborate on later).

Tieflings have since become much more popular in D&D, appearing in prominent roles in Baldur’s Gate III, and in a sense revitalising the possibilities of character design and development. Arguably the most popular companion, Karlach is a tiefling barbarian who is quite different from Annah in several ways, while also reflecting the same principles of how characters come alive and captivate players.

Love Stories

How players will actually engage with characters is unpredictable because players are unpredictable humans. Avellone notes how Annah’s temperament could have alienated players (and perhaps did alienate some players), but she still manages to come out on top as the most popular and most memorable companion and love interest. She might be the only romanceable character to ever nibble the player.

…we drilled down into the narrative aspects:

- We wanted another love interest – the “Betty” to Fall-From-Grace’s “Veronica,” even though those high-level Archie definitions don’t quite fit for either one. Fall-From-Grace seemingly has everything going for her (she doesn’t) and Annah is the opposite: it seems like she has nothing going for her (which also isn’t true).

- Annah provided a perspective on the slums of Sigil and also a tie to the major NPC Pharod beyond Pharod simply being a scheming NPC and made him something more than just a quest objective. Also, it was intended for the player to see (in her) her foster father’s manipulations, and the pain of being manipulated/leveraged that places on someone who has no one else in the world to call family.

And that is where her complexity really shines: when you understand she’s just a lost girl, caught up in an underworld beyond her control, and yes, she comes across as an abrasive, difficult individual, yet she becomes your most loyal friend. Of course, that involves putting up with her rough edges and daddy issues to a degree. In a word, true love, or at least what can be understood as true love in the world of Torment.

Inner Life

The secret ingredient is inner life. Characters cannot live in the service of the player and other companions; they must have their own thing going on as well. And in a world like Torment, they must, of course, be tormented by something: by feelings of inadequacy, a lack of belonging, orphanhood, and so on. Annah’s inner life springs from a place of empathy in Avellone’s character development process.

- … we wanted each companion in the party to be wrestling with something that had deeply wounded them emotionally. For Annah, it came from feeling outside of the world, someone who Pharod viewed as a tool to be cast away as needed, so she had to (indirectly) communicate that pain.

- Annah also utilizes a classic trope arc and it’s (1) two characters meet with evident hostility, (2) this hostility causes various dramas and conflicts, (3) the two characters bond, either over respect or affection or both, and (4) this one is key: you bonding with Annah causes her to be willing to fight to defend you… even to death. This hostility-to-life-loyal-kinship is something I happen to like in most media, as it’s usually a reward for the protagonist (you, the player) being loyal, just, sacrificing, caring… basically, all the heroic elements we strive for, except in the game, you can clearly see what the reward is in the end when you confront the Transcendent One. This is an arc that hits me strongly, so I wanted to include one into the game – and Annah was one of the representations of it.

Loyalty is perhaps one of the most persistent and flexible themes across literature, religion, politics, and popular culture in general. It sits right at the intersection of emotion, morality, and social order, standing out as a core value in social contexts. Annah’s loyalty to the player character, “even to death,” is tested in the final act.

Avellone’s thoughts and memories on this soon-to-be 30-year-old game and its cast of characters are especially valuable because they help us reclaim what we love in games as something more than killing-time entertainment, as more than an assemblage of words that could be generated by any NPC language model.

“What can change the nature of a man?” is a question that resonates and sits with us for years, even decades. In the second part of this interview, we’ll discuss how, once characters come alive, they must also, in their own way, change, live, and die.